Open Air Treatment Of Influenza

"The efficacy of open air treatment has been absolutely proven, and one has only to try it to discover its value."

Regarding Open Air Treatment: "Out of between 5,000 or 6,000 men on the ships, between 1,200 and 1,400 had contracted the disease; 351 of the most serious cases were treated at the tent hospital, of whom 35 died."

Regarding Traditional Treatment: "In one general hospital there were seventy-six cases; within three days, twenty of these cases died, and seventeen nurses were down with influenza."

Open Air Treatment of Influenza

William A. Brooks

Surgeon-General, Massachusetts State Guard

The following article, which appeared in the October 19, 1918 American Journal of Public Health, offers anecdotal information on the efficacy of open air—sunlight and fresh air—in the recovery from Influenza.

BEFORE much of this influenza appeared in Boston there were rumors of it, and then one or two cases appeared. Doctor Croke, who had charge of the ships connected with the Recruiting Service of the Shipping Board at East Boston, was instructed that if a case was found all the attendants were to be masked with gauze masks.

One Monday morning Doctor Croke reported that he was getting a great many cases of influenza. A visit was made to the ships in East Boston, where men were found scattered about on the decks and in their bunks. Apparently there were too many cases for the hospitals in Boston to accommodate in a hurry.

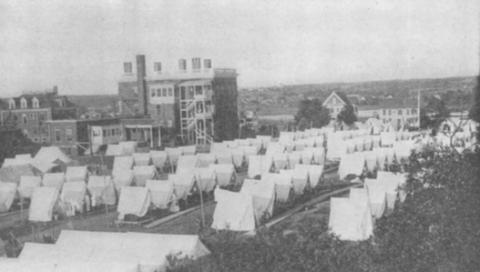

Mr. Henry Howard, director of the Recruiting Service, was seen and a plan was suggested to him to establish a tent hospital on Corey Hill with the assistance of the State Guard. Colonel Stevens, the adjutant-general of the Massachusetts State Guard, consented to call out the State Guard at the expense of the Shipping Board. Colonel Emery, at half-past two in the afternoon, was asked to provide tents and field equipment. Between half-past five and six o’clock the tents commenced to arrive at Corey Hill from Framingham. The Brookline Company of the State Guard was ready to erect them. Beds and hospital supplies were brought up from the Commonwealth Military Emergency Hospital. Laborers were obtained to make sewer connections and also to connect with the water supply. The State Guard medical officers were ordered to report and members of the Ambulance Corps with the ambulances came from the Commonwealth Military Emergency Hospital. Before midnight thirty-eight patients had been brought from East Boston and put to bed in the tents. For a few days the weather was bad, cold and rainy, making it extremely uncomfortable for the doctors and nurses. The tents, however, had been so thoroughly ditched by the Brookline Company that it is no exaggeration to state that the ground inside of the tents was kept perfectly dry. Within a few days many cases of pneumonia were brought to the camp. The attending physicians were greatly puzzled, for the pneumonias did not seem to be of the type which are generally met with. The patients became greatly cyanosed and the ordinary heart medicines like digitalis and strychnine apparently had no effect, and seven or eight deaths occurred in rapid succession. The attending physicians became much discouraged. Meanwhile Doctors Slack and Overlander were busy taking cultures. They soon reported that the influenza bacillus predominated in these cultures. They also found that both Type I and Type III of the pneumococci were present. They also found streptococci. Their reports indicated that the present epidemic was a mixed infection.

In getting the history of the cases, Doctor Harrington found that the worst cases of pneumonia came from that part of the ships where the ventilation was the worst. Doctor Slack’s analyses clearly demonstrated that we had to deal with the pus-producing pneumococcus. We were able to get reports from the autopsies at the Naval Hospital, showing that the men died, not from heart failure, but from abscesses in the lungs. This explained why the heart stimulants had had practically no effect on the cyanosed patients, and that they died, not from heart failure, but from lack of air.

The medical staff thereafter determined to give the patients all the air possible. Thereafter, on pleasant days, every patient was taken out of the tents and put into the open.

From the first day, the results were startling. Almost every patient without exception had a lower temperature at night than in the morning, and felt decidedly more comfortable. The charts of these patients are very instructive and clearly demonstrate the great value of plenty of air and sunshine for patients suffering from influenza and pneumonia. From being discouraged, the medical staff became enthusiastic, and the patients were treated with the confidence that at last something had been found which would give good results.

At the end of three weeks the epidemic on the ships was practically under control, and in a few days over four weeks the tent hospital was closed. Out of between 5,000 or 6,000 men on the ships, between 1,200 and 1,400 had contracted the disease; 351 of the most serious cases were treated at the tent hospital, of whom 35 died.

Very few of the attendants and nurses contracted influenza while working in the tent hospital. One nurse who worked for the first two days, and undoubtedly had contracted influenza before coming to the camp, having been exposed to it in her own home, died at one of the hospitals in town. Another nurse died at another hospital in town.

The following facts were deduced from the experiences of the first tent hospital:

Period of Incubation.—Apparently it varies, averaging about two days. Sailors at work would be feeling perfectly well and then be suddenly stricken. Others would be ailing and then gradually come down. Fatigue seemed to play an important part.

The infection itself, as has been stated previously, was a mixed infection; and where Type III of the pneumococcus predominated many of the cases were fatal. In many of the cases of pneumonia, the diagnosis was made by Doctors Slack and Overlander from the sputum before any signs could be detected in the chest.

Medical Treatment.—Very little medicine was given after the value of plenty of air and sunshine had been demonstrated. Practically only three drugs were used: Dovers powder, some form of aspirin, and iodide of lime in one-third grain doses. The patients were fed every two or three hours, and given a variety of food with plenty of fruit. They were also made to drink plenty of water. Their feet were kept warm with metallic hot water bags, or else by means of heated bricks wrapped in newspapers. Owing to the danger of leakage, rubber hot water bags were avoided as much as possible.

Mask Technique.—Before the tent hospital had been established very long, it was found that the ordinary masks made out of a number of layers of gauze were very unsatisfactory. Nurses and attendants were constantly dropping the masks, and replacing them with the wrong side next to the mouth and nose. Improvised wire masks were made out of ordinary gravy strainers. The strainer was shaped to fit the nose, and five layers of gauze were simple basted on to the wire frame. No attendant or nurse was allowed to go near a patient unless wearing one of these masks. The gauze on the masks was changed every two hours. It was found impractical to sterilize the mask with the gauze on, owing to the fact that in the process of sterilization a great deal of the fuzz on the gauze was removed and it's value as a strainer was diminished. Nurses and orderlies were instructed to keep their hands away from the outside of the masks as much as possible. Every wearer of a mask was inclined at first to wear the mask too high up on the nose and a great deal of discomfort was caused by this. The upper end of the mask should simply rest above the nostrils, and the lower part should come under the chin. The two tapes on the masks were tied over the ears at the back of the head or neck. There was a superintendent of masks whose duty it was to see that all the masks were changed every two hours, and to see that they were properly sterilized and fresh gauze put on.

Technique of Hands.—Every nurse and attendant was cautioned that, after working over patients, the hands should be washed thoroughly either in 1/1000 corrosive sublimate solution, or in a solution of triple lysol. Before going to mess it was required of all nurses that they wash their hands and then go directly to mess.

Observations.—There is apparently a great opposition among many of the medical fraternity against open air treatment. Many of them seem inclined to think that, if the windows of a room are open, the same object is attained. Many think that the ordinary sun parlor of a hospital is “just as good.” The facts are, however, that the patients do not thrive as well in any ordinary hospital, no matter how well it is ventilated, as they do when they are put right, out into the open. The objection to the sun parlor is that one gets direct sunlight only during part of the day, whereas the patient who is out in the open gets the direct sunlight all day long. Certainly these results warrant medical men in visiting these camps to go over the records, examine the charts, and hear what the patients have to say in regard to the good effects of open air treatment.

The efficacy of open air treatment has been absolutely proven, and one has only to try it to discover its value. It represents the result of study by twelve or fourteen men, who, for a month, practically devoted their entire time to influenza and its complications. Compare the following data with the results cited above, obtained from open air treatment: in one general hospital there were seventy-six cases; within three days, twenty of these cases died, and seventeen nurses were down with influenza.

William A Brooks, American Journal of Public Health, October, 1918, pp. 747-751.